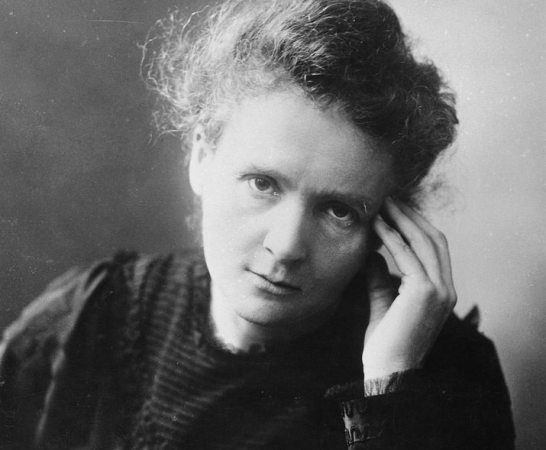

Celebrating Super Heroines of Science

Our team and twitter friends shared stories of women in STEM who have made an impact on them. From pioneers such as Ada Lovelace, who in 1842 designed the world’s first computer, to scientists likes Rosalind Franklin and Dorothy Hodgkin – women have always been behind – and in front of – major STEM advances around the world.

Banners were created by young people from our Maker Club for the 14-18 Now ‘Processions’ living artwork celebration last June by cultural organisation, Artichoke, and as part of a year of celebrations to mark the centenary of Votes for Women.