Good news about our great (crested) newts

Wednesday 3rd May 2023

We love the energy of the awe-inspiring daytime activities at the Science Oxford Centre, but when the lights go down, between dusk and dawn, another world, just as wonderful, comes to life. The pond and woodland around the Centre are home to a number of nocturnal creatures, who start their ‘day’ after we’ve all gone home. Great crested newts are among them and, good news, they seem to be thriving.

A protected species

Protected by law, great crested newts (Triturus cristatus) are special residents of our site. The number has dwindled across Europe and the UK over the past decades as intense agriculture and expanding urban developments have disrupted their habitats. Laws are in place to protect the species, including their habitats, to give them the best chance to recover. Any activities that affect the newts and their habitats can only be carried out by a licensed ecologist, and unlicensed individuals can be fined or prosecuted.

In 2016, prior to the development of the Wood Centre for Innovation and the Science Oxford Centre, repeated newt surveys identified a medium-sized population of great crested newts in and around our ponds. During the development of the site, special precautions were put in place to ensure the newts and their habitat would not be harmed.

Training students

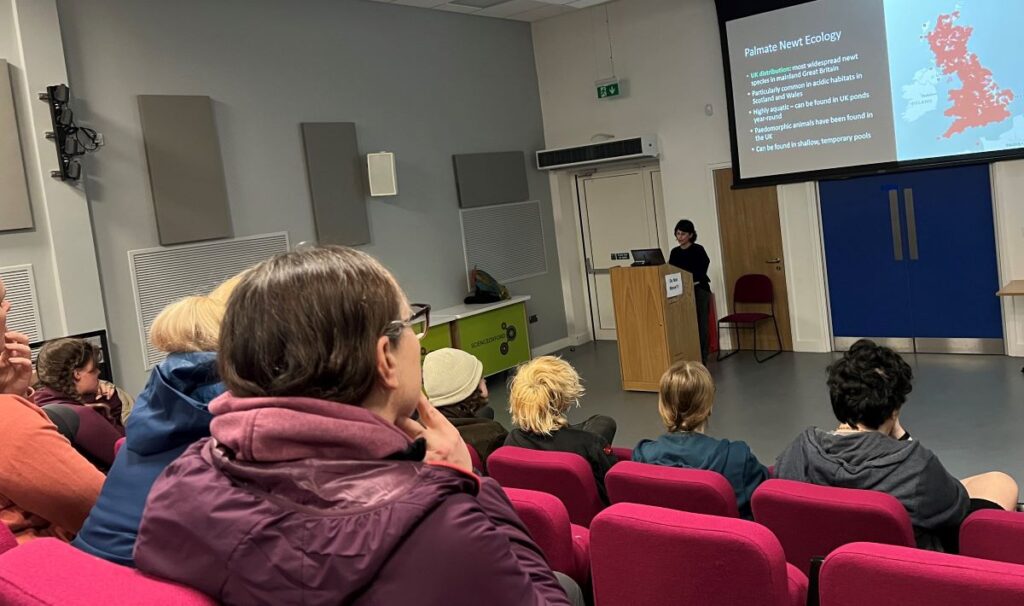

Having a known population of great crested newts makes the Science Oxford Centre the perfect location for students to learn about the practicalities of newt surveys. Recently, our centre hosted a training course for a cohort of Oxford Brookes University BSc (Hons) Animal Biology and Conservation students led by licensed ecologists from Oxfordshire environmental consultancy firm Turnstone Ecology.

Newt surveys involve the assessment of habitats and populations using a range of techniques. These include traditional methods of live traps, torchlight searches in and around water, searches of refuge and resting places, and egg counts. While focusing on the protected great crested newt species, such methods also assess their less rare, but equally wonderful, amphibious relatives.

DNA detection methods have also been developed, but these have the limitation that they only show whether the newts are present or absent, but do not show how many.

Using a number of survey methods provides an estimate of the overall population, which will inform decisions around the ecological management of a site.

Being amphibious, newts only spend part of their lives in the water, where they go for one main reason – to reproduce! The peak breeding time for these nocturnal newts is around mid-March through to June, when they gather around still waters like our ponds and females carefully spend their evenings laying eggs. So, this is a good time of year for students to be learning about newt surveys.

Egg count

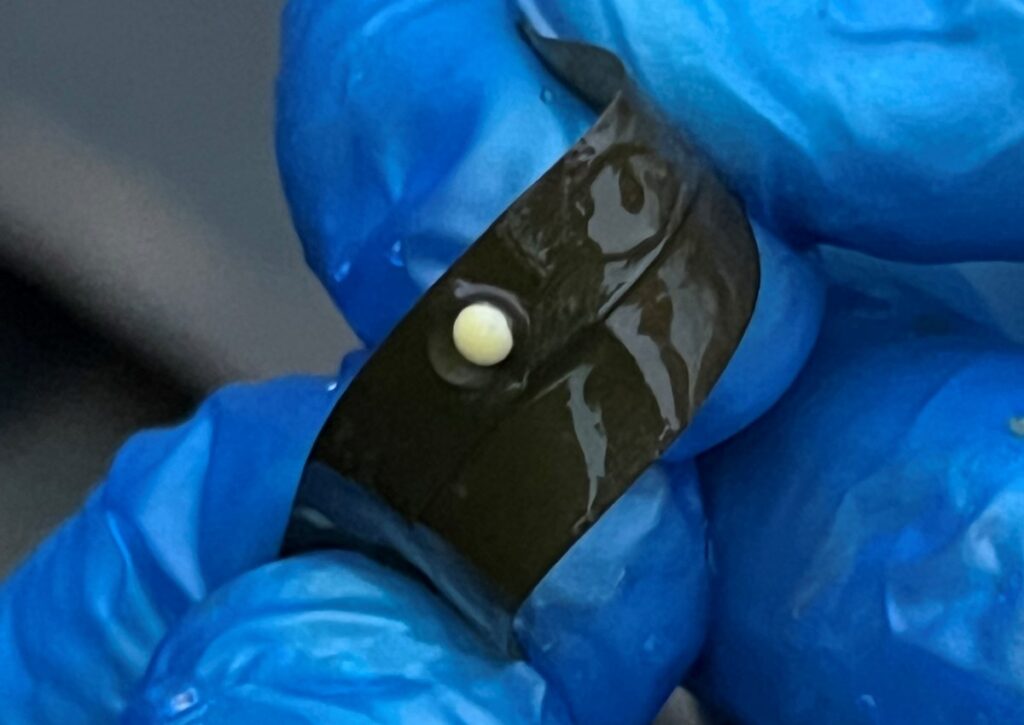

Before dark, they undertook an egg count. This requires a close look at vegetation on and under the water. Female newts lay hundreds of eggs in a season, but instead of laying spawn like frogs and toads, they lay them individually and carefully wrap each egg in a leaf with their hind legs. The eggs of great crested newts are creamy-white and about 5mm in diameter, while other newt species’ eggs are brown and smaller in size.

Live traps

As dusk approached, a number of live traps were installed in the shallows around the ponds’ edges. These simple traps prove irresistible to the newts who find their way in but then can’t get out and have to wait for assistance.

Torchlight count

As the Sun dipped below the horizon, the final survey technique of the evening began. The great crested newt is one of three native species of newts in the UK*, but it is possible to identify them by torchlight if you know what you are looking for. They are the largest of the species, are dark in colour (black or olive green) and have a bright orange belly with black spots. The males have a wavy (great) crest along their back and a bold white stripe along their tales. Using powerful torches, the group searched the shallows from the bank counting each and every newt before retiring for the evening.

However, that was not the end of the training – remember those traps?! At dawn the next morning, the students returned sleepy-eyed to count and release the temporary captives safely back into the water.

Results

Previous surveys, undertaken in 2016, found small and medium populations. In 2021, environmental DNA samples confirmed the newts were still present. This is the first population assessment we have undertaken since. Based on this survey, the population of great crested newts at the Science Oxford Centre is ‘exceptional’ having counted well over 100 great crested newts, and similar numbers of smooth newts, in a single visit.

Good habitat management

We should always be careful to interpret results in isolation, but this encouraging increase in breeding adult populations, combined with the habitat improvements we have made across the site, including the construction of hibernation piles, provision of corridors between ponds and changes to the ponds themselves, suggest that these woodlands suit our amphibious residents perfectly.

While this protected species warrants particular mention, these improvements are of course likely to have benefits for many other species found across our seven hectares of outdoor space. We hope to continue to encourage species and habitat diversity across the site.

Protecting local biodiversity

You too could make a difference to biodiversity. If you have a pond, make sure to keep some of the area around it wild with some logs, rocks and vegetation for newts or other residents to hide under. If you are lucky, you might see some newts of your own gathering in the water next spring. Such small changes in the local environment contribute to improvements in biodiversity more broadly and across the planet. What steps could you take in your garden, school or park to add to the collective effort to protect global biodiversity?

*The other two species are the smooth (or common) newt (Lissotriton vulgaris) and the palmate newt (Lissotriton helveticus).

Photo credits: Dr Roger Baker

Feature image caption: A great crested newt found around Science Oxford Centre ponds